Local birder Alma Chasez was kind to send us a list of birds that can reasonably be found, on a seasonal basis, in the Manchac Greenway:

American Bittern

American Coot

American Crow

American Robin

American White Pelican

American Wigeon

Bald Eagle

Barn Swallow

Barred Owl

Belted Kingfisher

Black Crown Night Heron

Black necked Stilt

Black Vulture

Blue grey Gnatcatcher

Blue Jay

Blue winged Teal

Brown Pelican

Brown Thrasher

Carolina Chickadee

Carolina Wren

Cattle Egret

Cedar Waxwings

Chimney Swift

Chipping Sparrow

Common Loon

Common Moorhen

Common Yellowthroat

Double Crested Cormorant

Downy Woodpecker

Eastern Bluebird

Eastern Kingbird

Eastern Phoebe

Eastern wood Pewee

Fish Crow

Flicker

Flycatcher species

Forster’s Tern

Gadwall

Golden crowned Kinglet

Grackle species

Gray Catbird

Great Blue Heron

Great Egret

Great Horned Owl

Green Heron

Green winged Teal

Hairy Woodpecker

Herring Gull

House Sparrow

House Wren

Killdeer

Laughing Gull

Least Bittern

Lesser Scaup

Little Blue Heron

Loggerhead Shrike

Louisiana Waterthrush

Magnolia Warbler

Mallard

Marsh Wren

Merlin

Mourning Dove

Northern Cardinal

Northern Harrier

Northern Mockingbird

Northern Parula

Northern Pintail

Northern Shoveler

Nuthatch species

Orange crowned Warbler

Osprey

Pied-billed Grebe

Pileated Woodpecker

Pine warbler

Prothonotary Warbler

Purple Martin

Rail species

Red bellied Woodpecker

Red eyed Vireo

Red headed Woodpecker

Red shouldered Hawk

Red tailed Hawk

Red Winged Blackbird

Redhead

Ring necked Duck

Ringbilled Gull

Rock Dove

Ruby crowned Kinglet

Ruby Throated Hummingbird

Sanderling

Snowy Egret

Song Sparrow

Summer Duck

Summer Tanager

Swallow tailed kite

Tree Swallow

Tricolored Heron

Tufted Titmouse

Turkey

Turkey Vulture

White eyed Vireo

White Ibis

White throated Sparrow

Winter Wren

Wood Duck

Wood Thrush

Yellow bellied Sapsucker

Yellow Crown Night Heron

Yellow rumpled warbler

Yellowlegs species

There are other birds that will pass through on a migratory basis that I have not included because they may be there a day or two and move on.

Alma

Great Blue Heron:

Hunting on the edge of the water, the Great Blue Heron (Ardea herodias) stands stock-still with a steady gaze. Suddenly, it uncurls its long neck and jabs its pointy beak to grab fish, frog or insect making the mistake of coming too close.

These majestic birds are one of the largest birds of prey in Louisiana. The long-legged wader stands up to four and a half feet tall and can have a wingspan of over six feet. They are beautiful to watch in flight, gliding serenely up and down the bayou from one favorite hunting spot to another, seemingly floating along as they take measured strokes. One of their secrets is that in spite of their great size, they weigh only 5 pounds.

If you happen to surprise one of these big birds you’ll be scolded with a loud, gruff squawk as they leap into the air to fly away. It’s an agitated kind of sound and the bird seems to emphasize its displeasure at your interruption by simultaneously lightening its load by ejecting the contents of its intestines.

Most of the time we see this bird alone by itself, but they do have a social life. During breeding season in early spring they take a partner with whom they do a little dancing, necking and staring straight up into the sky together. The couple usually occupies a previously used stick-nest high up in a tree, often with other nesting couples nearby. This rookery is referred to as a “heronry” by birding professionals. When the young are sufficiently raised up, the bird resumes the solitary life.

Brown Pelican:

Although they don’t show up much on the Greenway, preferring the wide-open spaces toward the saltier end of Lake Pontchartrain, they do make an occasional showing on Pass Manchac and Lake Maurepas. Like the Bald Eagle, the Brown Pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis) has, in the span of a human lifetime, made a tremendously successful recovery from the devastating effects of the banned pesticide DDT and are now quite commonplace in coastal Louisiana.

Awkward on the ground, they are a graceful sight in the air, skimming just above the waves or soaring in the skies high above. Drivers on the Lake Pontchartrain Causeway routinely see them deftly gliding effortlessly for miles along the bridge railing, riding the wind banking off the side of the bridge.

They are also consummate fishers. They’ll make a spontaneous dive into the water to pounce on fish they’ve spotted from the air and scoop them up in their ample pouch. It’s also fascinating to watch how they show a remarkable degree of cooperation when a gang of seven individuals advance together side-by-side through quiet water and as if on a silent command, quickly surround and dive on the baitfish they’ve corralled to regroup and do it again.

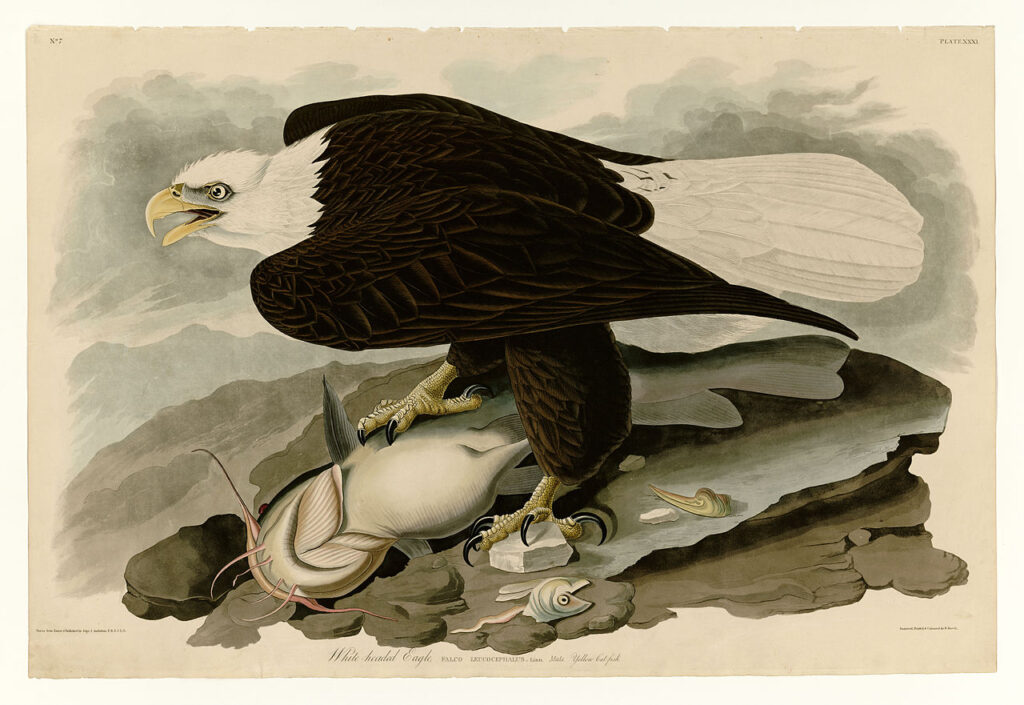

Bald Eagle:

The Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) has been quite a success story in the swamps of Louisiana. In the 1960s a near-zero population of this species was caused by the ill-effects of the banned insecticide DDT. As this began to disappear from the environment, the bird began to slowly recover, but it wasn’t until the 1990s that they once again became a common sight in this region. These days it’s not unusual at all to enjoy a by-chance sighting of one suddenly appear, skimming above the trees on the Manchac Greenway or perched in a tree branch overlooking a waterway or seeing one of their massive nests atop a stark tree trunk in the distance. With extensive wetlands, lakes and productive fisheries, Louisiana and Florida have become the two main population centers for the bird in the Lower 48.

Other birds with large, majestic wingspans seen soaring above the Greenway include Osprey, Golden Eagles, Red-tailed Hawks and Vultures – but the Bald Eagle is the one with an unmistakable white head and tail with a dark brown body and wings in between.

Great Egret:

Egrets (Ardea alba) are a common sight to Louisiana natives but imagine what impression they must make to someone unaccustomed to seeing a large, exotic-looking, pure white bird hanging out close to humans, hunting in roadside ditches or elegantly flying above suburban streets.

Their slender neck, usually coiled in a graceful “S” when standing or in flight, stretches out straight to catch and gulp their prey. They adroitly toss their catch – mostly small fish, crustaceans and amphibians – into the air, catch it and reposition for swallowing.

Egrets are a big bird in stature only The stand two feet tall with a three-foot wingspan but weigh only about three-quarters of a pound.

They usually find an isolated spot to roost together for the night up off the ground. They seek even more remote locations to build their rickety nests in trees for group breeding. It’s an awesome sight to come across dozens of their stark white forms nesting together deep in the dark cypress forest off of the Manchac Greenway.

Ibis:

American White Ibis (Eudocimus albus) live in wetlands across the breadth of the Gulf Coast. They like to graze in shallow-water muck, like that found in this area’s marshes and swamps, by using their curiously curved beaks to winnow out small fish, worms, insects and crustaceans (mainly crawfish). They do this activity largely in secret, away from Man’s prying eyes, however, they show off for all the world to see when they travel in huge “V-shaped” flocks during the year; traveling either Eastward or Westward, paralleling the coast to jump from one grazing or nesting site to the next. Unfortunately, over-development by humans on this coast has robbed them of their habitat, causing them to have either fly further or remain in isolated pockets.

Osprey:

The Western Osprey (Pandion haliaetus) almost exclusively eats fish, thus, they’re also known as “sea hawks,” “river hawks” or “fish hawks.” (If you want to get fancy, call them “piscivores,” or if you want to get even fancier, use the Greek term “ichthyophagous.”)

In the area around the Manchac Greenway the Osprey rivals, and is probably more numerous than the Bald Eagle. They are similar in size and shape but the eagle is less discriminating in its diet, having been known to attack and eat a wider range of creatures from land, sea and air. Flocks of Bald Eagles are even known to mob landfills to scavenge food.

Ospreys are dark brown on top and have whitish heads and undersides with a distinctive layered “check” pattern in these feathers. Their plumpish, nearly grown fledglings have a golden hue to their feathers that disappears on full maturity.

Like the Bald Eagle, the Osprey and its life-partner build huge, high nests of sticks and branches. If enough tall trees aren’t available, electric transmission and communication towers are fair-play as far as these birds are concerned, and this behavior has been known to cause problems for humans. Artificial towers have been set up by conservation groups in parts of the country where they are trying to encourage this species and keep the electricity on.

Red-winged Blackbird:

One of the loveliest sounds you’ll hear out in the expansive Louisiana marsh is the sweet, trilling song of the Redwing Blackbird (Agelaius phoeniceus). While the wind rustles the tall grass, their song can be heard from every direction as they flit from here to there, hunting or perching on a high vantage point to guard their territory.

A certain number of Redwings stay year ‘round and a certain number yo-yo up and down the continent each year. They follow the warmth of the new season, feeding on seeds leftover from last fall as they make their way back to their northern summer homes.

The glossy black Redwing males are easy to recognize because of the flashing diagonal red and yellow bars on their shoulders, and of course, by their call. The mostly monogamous females in their company are slightly smaller and a brownish black with white streaks on their breast.

The secret to the Redwing’s pretty song, and of any bird’s voice, is down their throat in a piece of equipment called a “syrinx,” the avian equivalent of vocal cords. Depending on the species its manipulation can make a beautiful sound (ex. whippoorwills) or not so beautiful (think crows).

Vulture:

Vultures are magnificent in flight, soaring effortlessly high above, light as a kite, with wings spread wide and taut. They have only to make subtle moves with these wings, hardly flapping them at all to stay aloft on the breezes forever. As they wheel about this way and that, they’re cruising for just the right scent – the whiff of rotting flesh wafting from the land below. They then spin down for a communal meal with friends.

These scavengers are part of Mother Nature’s “Cleanup Crew,” a none-too-proud fraternity scouring the surface of the Earth to clean up bio-hazards before they get out of hand. Unlike many animals who take only an occasional carrion meal – raccoons, lions, crows, dogs, flies, wolves, bears, owls, hyenas, etc. – vultures feed almost exclusively on the dead. They are considered such an integral part of the ecology they are a protected species under a 1918 federal law. Pretty in the sky, they are ugly specimens up close with disgusting eating habits but serve a worthwhile purpose in nature’s complex food chain.

Two birds of similar size, shape and mission soar over the Manchac Greenway, the Turkey and the Black Vultures. The back of the wings and tail of the Turkey Vulture (Cathartes aura) are light grey in color and the American Black Vulture (Coragyps atratus) is light grey on only its wing tips. Both scavengers share the same repulsive diet, traits like having no voice except the occasional grunt or hiss and naked heads. Neither will win an avian beauty contest – Cathertes is red-headed like a Turkey and the Black Vulture’s head is covered with wrinkly, grey skin.